Last November I watched The Queen's Gambit, and it was excellent enough to motivate me to learn chess. My only experience with chess then dated back to my teenage years when I looked up the rules of how the pieces moved, tried a few games against the computer in the easiest possible mode, lost all of them, at which point I decided that this game was stupid. But Beth Harmon got me motivated, and I wanted to give it a more serious try, and there I discovered my new favorite pandemic hobby.

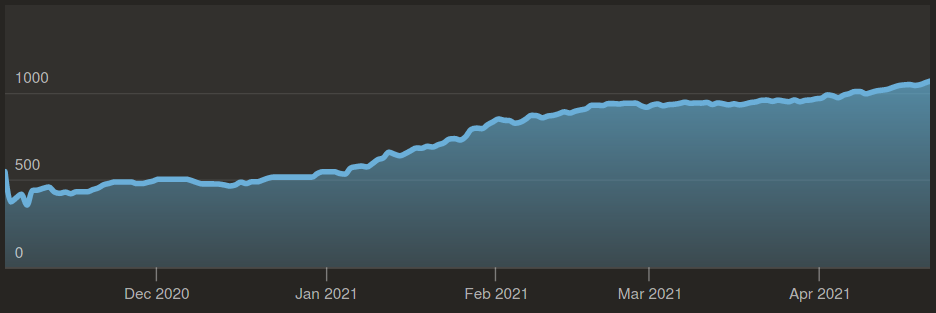

I've now crossed the rating threshold of 1 000, and here I am doing a bit of journaling. There are plenty of technical resource on the Internet on how to get good at chess, so I won't be giving any such advice here, but will focus on general things I've learned which might be interesting to beginners or even non chess players.

If I was to describe what is a level 1 000 player according to my self-evaluation (of my top form), it would be something like: If the situation is simple I can play the best move. If the situation is complicated I'll most likely play a bad move. Otherwise, I'm able to elect a few candidate moves that are reasonable, but because I don't have any sort of strategic view of the match, I don't really know which one to play.

Experience matters so much

Initially I had this idea that chess was some sort of scientific game in which you could win if you were clever enough — some sort of advanced IQ test. The reality is far from it. Sure, you need to be able to get focused, think deeply, and make a bit of calculation in your head, but my experience so far is that chess is mostly about pattern recognition. That is, training your brain to recognize patterns indicating that you're in a danger, or that there is an opportunity to gain advantage over your opponent, etc. The game is simply way too complicated to get it right by the sole power of thinking.

This is especially true when you begin. At this point, there is a limit to where concentration can get you, even for simple things like not losing your pieces in stupid ways. You need to blunder, blunder, and blunder again until your brain naturally integrates the game's dynamic, at which point an alarm bell start ringing when one of your pieces is under attack, and it becomes way easier to play correctly.

My most important realization was watching grandmasters commenting live while they're playing on YouTube, and seeing how important instinct is in their decision process. This "instinct" is the result of all their games played, which makes them (consciously or not) recognize patterns they've seen before, and knowing how to react. At a beginner/intermediate level, this is mostly about not hanging your pieces, spotting possible checkmates, identifying opportunities for tactics, and so on.

On my way to 1 000, I've blundered in the most bizarre of ways (what could be called "brain bugs"). At some point around 800 I would be proud to position my queen in front of a rook, thinking that I was pinning the rook to my opponent's king. Not much later I would try to fork my opponent's king and knight with my own knight. My most recent brain bug is forgetting that my pawns can take pieces, so sometimes when my opponent is exchanging a piece I think that I've just lost the piece. I have no solution to those brain farts other than playing until each one of them is consumed and gone for good.

Safety is hard to evaluate

In many real life things, there is an idea of margin of safety. For example, if you walk near the edge of a tall building, then there isn't much margin of safety on the danger of falling. Sure, you're gonna be careful where you walk, but what would happen if a strong wind suddenly arise? Or if a mad person pushes you? Now, if you distance yourself many meters from the edge, you're adding a margin of safety, which protect yourself even against those unlikely events.

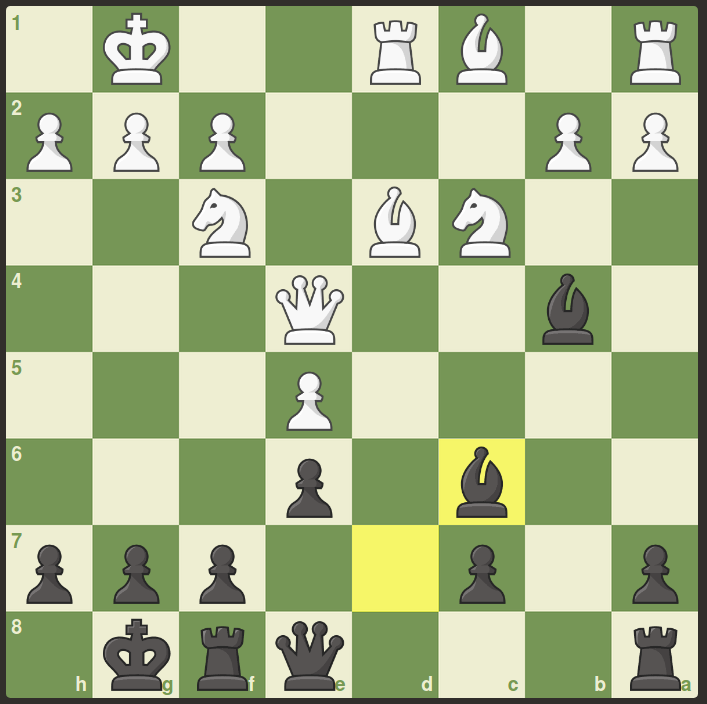

In chess, you want safety for your king, and it's of course most comfortable if you can have it with some margin. An example of no margin of safety would be "my opponent can checkmate me on his next move", where you're forced to do something to avoid this terminal fate. But you have in fact already some chess level if you're able to spot that you're in such danger in a first place! For the simple reason that sometimes it looks like you're safe with margin, but it turns out that you were no safe at all! The usual clues that the brain is looking at to evaluate safety can be very misleading in chess. There are 2 specific patterns that I've identified (and surely many more I've not yet):

- Thinking that you're safe because of the "visual" reinforcement around the King. The idea is that in real life if you want to protect a king you mostly need to have a lot of bodyguards around him. Bonus points if the enemy is far away. Of course, chess is harder than that.

- Thinking that you're safe because you're much "wealthier" than your opponent. At a beginner level, lots of blunders and mistakes happen, which can result in very polarized games where one side takes complete advantage over the other side, this advantage being materialized by having more pieces ("material") than the opponent. If you're the one having the advantage in such moment, it seems like you're invincible, and that whatever you do, you can't make a mistake that would be big enough to dethrone you from your supremacy. Wrong, wrong, wrong. It's actually very simple: the minimum number of pieces needed to deliver a checkmate is 2 (it depends on the pieces, but Queen+King or even Rook+King are well-known fatal combinations if you can't or don't defend them). So it's not over until it's over.

Wishful thinking will lose you

I would say that it's good to have hope in life, that is, to wish that things will go for the best. However, problems will start to appear if you're using what you hope for to actually plan the future. I think this is an application of wishful thinking, although the notion of tunnel vision is also often used in chess commentary.

In chess, when you calculate possible outcomes of a move you're considering, you must make hypothesis about how your opponent will respond. At this moment, you can wish for your opponent to respond in a way that is convenient for you, and it is very tempting to transform that wish into a tactic. Obviously, your opponent is under no obligation to play according to your wishes, and in practice they won't. They will only punish your hope. So what you should do instead is think about how your opponent could reply with the move that would be the least convenient for you, and discard any move that can result in a disadvantage because of such possible response.

At low ratings, wishful thinking can actually be productive, because your opponents don't play accurately, so this allows you to take shortcuts that would otherwise be punished harshly. But as you progress, wishful thinking becomes more and more catastrophic, because your opponents are more and more able to find the best replies to your moves.

So, basically: plan for the worst, and don't take any chances.

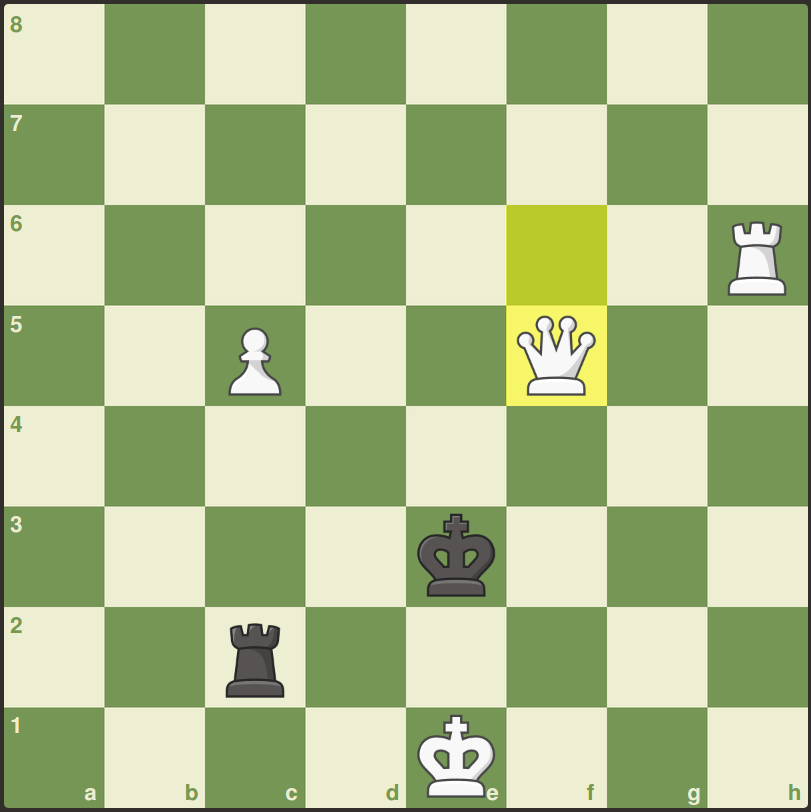

There is one specific kind of situation where you can think wishfully: a losing endgame. At this point, your only hope is that your opponent will make a mistake, so you can set traps up and hope for your opponent to fall for them, even if those traps could turn against you with a vengeance (the worst that can happen is that you'll lose faster, which doesn't affect the result). This is one area where chess engines are weaker than humans, because chess engines assume their opponent play perfectly, which disallows risky traps. Not that it makes any difference for them since chess engines rarely end up in a losing endgame. However, you should always take the accuracy evaluation of your moves by an engine with a grain of salt if you were playing a losing endgame.

Elo is Hell

The activity of chess is equipped with a tool which originates directly from hell and whose goal is to rank every single player in the world on one axis from top 1 to bottom 1. This tool is the Elo rating system, whose name comes from Arpad Elo, the inventor of such system. The algorithm behind this system takes 2 rating values involved in a match, and, according to the outcome of the match (victory from one side or draw), affects a new rating to the 2 players. If you win against someone your rating, you win some bit of rating (he loses some bit of rating). If you win against someone higher than you rating, you win big time (he loses big time). And so on.

If you take a look at various online communities (/r/chess, YouTube, etc), you realize how much players are obsessed with their rating, as if it is the definition of their entire chess identity. The anxiety induced by this obsession is well-documented on Reddit and posts about it comes up regularly. YouTube is on it too.

My experience is that this is particularly true with online chess when you play against strangers you know nothing about except a pseudonym. Clearly the most fun games of chess I've played are the ones over an actual board against my sister at Christmas, and the ones I played online against a friend who is rated 1,500, who beat me 3 times in a row, but which was extremely exciting, educative and fun. I actually defended quite well in those matches and we both had an accuracy of above 80%. I think playing against someone I knew made me way more solid than the usual because there was extra-stimulation to show him that I had some level.

Another thing to take into account is that ratings are variable across platforms (Lichess is known to have inflated ratings in comparison to chess.com), and also variable across time controls on the same platform (10-minutes games are way more popular and therefore less demanding than say 60-minutes games).

Finally, because your victories and defeats depend a lot on your level of fatigue, your mood of the day, etc, you need many many games until all factors gets blended together and it levels off to your "true" rating. In this respect I think one of my strengths is my consistency. If you look at the graph at the beginning of the article, there is no roller-coaster business going on, it's just one smooth evolution. There are 2 ingredients to it: regularity (I play one game everyday), and focus (when I play this game I eliminate any distraction and play seriously).

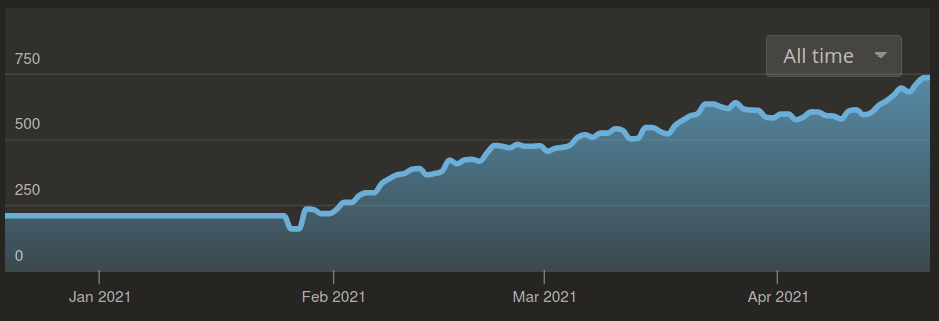

This discipline is not always exciting (although productive and intellectually satisfying), so I have a get-away which I use to have the most fun at chess: blitz games. The 2 ingredients of my blitz games are: irregularity (I play many blitz games in one row then will stop for some days), and distraction (I put on some music, and play fancily, looking at what happens if I sacrifice some pieces or stuff like that). Without much surprise, Elo evolution is more roller-coaster-like on my blitz game.

I think it's important for anyone to have a space (like my blitz games) where they can play chess without feeling that there are any stakes at play. Think about it this way: games in which Grandmasters see their rating affected happen on a few occasions in one year. The rest of year, they play hundreds of games (as part of their training, or in unrated tournaments) where their official rating is not affected. Like a Grandmaster, you are also entitled to play chess without being always in the scrutiny of your rating. So, use a side account, or play a different time control, or whatever, then decide, at your will, when you play a game that will impact the rating that you consider to be your "official" one. For me, it's one game per day. It can be more, it can be less. It even can be none, if you only want to have fun.